Getting free – leaving a violent partner c1960-1990

Content warning: this post contains description of domestic abuse. Please read with care – information on where to find support is listed at the end of the post.

“Why doesn’t she just leave?” This question, frequently asked about women living with violent men, is loaded with incomprehension and, sometimes, barely concealed frustration. The question also minimises women’s experiences of abuse and distances the questioner from its realities. This is a million miles from what it’s really like. It assumes that domestic abuse is a one off or occasional instance of physical abuse or assault and that leaving is an event rather than a process often undertaken over a long period which usually includes several attempts. Focussing on what women should do is a common response to men’s violence against women and for many, obscures the risks and reality women face. Between 2009 and 2019, 112 women were killed in Scotland by their partner or ex-partner – that’s nearly one woman every month.

‘Of the 888 women killed between 2009-2018 in the UK at least 378 (43%) were known to have separated, or taken steps to separate, from the perpetrator. he vast majority (338, 89%) were killed within the first year and 142 (38%) were killed within the first month of separation, or when the victim first took steps to separate even if she had not actually left the perpetrator. In some cases, the perpetrator appears to have killed the victim when he discovered that she was planning to leave him.’

Femicide Census – UK Femicides – 10 year report 2009-2018 p.30

Leaving an abusive relationship has never been easy and is usually dangerous. This blog, based on my oral history research into domestic abuse in post-war Scotland provides some insights into why women couldn’t just up and leave a the first hint of danger.

A previous blog in this series looked at police responses to domestic abuse. It provided one side of a story and showed that women’s fears of seeking help from public agencies were not unfounded. What follows looks in more detail at why leaving was so difficult for women.

Fear was the dominant factor in the women’s lives. Fear of the consequences of their actions, inactions or words and the unpredictability of how these could be interpreted by the men they shared their lives with.

I was frightened of being hurt. I was frightened of his power… I was frightened that something would happen and I’ve never forgotten that, living in fear all the time.

I was completely fearful all the time because anything that I said could trigger a reaction.

With family privacy sacrosanct, approaching public agencies was out of the question, and remaining silent about the abuse was the only option. Living with the fear and reality of violence and the unknown consequences of public disclosure created a tight physical and psychological web around women held tightly in place by the debilitating physical and psychological impact of the abuse itself.

The physical impact of domestic abuse

Domestic abuse was the main cause of physical injury in the women’s lives and was a key factor in a range of physical and emotional symptoms they experienced. Some suffered serious facial injuries: black eyes, serious eye injuries, broken noses and chipped cheekbones were common. Two women needed substantial reconstructive facial surgery following severe assaults.

He beat me within an inch of my life and I believe, and I know, that if that neighbour hadn’t phoned the police that night I would have been dead. I was unrecognisable. The hospital had actually to slit my eyes open.

Some of the women developed long-term illnesses such as peritonitis; gallstones; auto-immune diseases. Others recalled being confined to bed for prolonged periods with undiagnosed illnesses, living with severe pain and extreme fatigue.

‘Constant, severe assaults cannot be endured without emotional effects. Chronic emotional distress is a normal, not an abnormal, reaction to this kind of treatment.’ [i] The women also described the cumulative impact of living with stress over many years.

The stress related stuff affects you. All I could do was lie in bed and cry for days. I was in agony and I couldn’t make the decision to phone a doctor or an ambulance…I just lay and cried and it was six weeks before I even saw a physio and I never got an X-Ray and as I say I’m still having problems with it.

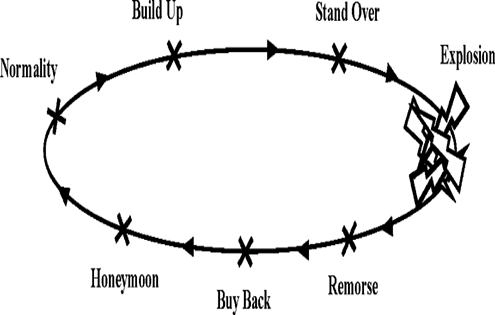

Women experienced ‘cycles of violence’– repeating loops containing periods of calm almost companionate marriage. These were followed by a build-up of tension leading to outbreaks of abuse and violence then remorse, apologies, contrition and another period of calm. The periods between the stages of the cycle might last weeks or months, but the pattern was consistent.

The emotional and psychological impact of domestic abuse

This took a severe toll on women’s mental health.

I remember thinking ‘I’m losing my mind… he was nice last week, what’s he doing this week’?

You think you’re goin’ off yer head because there would be times when he would be horrible and then he would be making up. He was like Jekyll and Hyde,

The women were unable to make sense of what was happening, saw no logic in it and with no opportunity to discuss it with others, they internalised it.

I internalised it, as I suppose a lot of people do. I mean you either go one way or another, you either go out and you’re angry with the world or you internalise it.

Internalisation involved absorbing the shame as the men chipped away at their self-esteem. A great deal of the abusive rhetoric was focussed on the women’s behaviour, domestic work, their appearance and competence.

At first I started to actually hate my mother ‘cos…she’s no tellt me how tae cook. Then I began to feel absolutely worthless. Then I went very into myself, I was a nervous wreck, I was a bag of nerves.

It’s the things that they do to your self-esteem they just tell ye how useless ye are.

This is all my fault and I’m an idiot….I felt let down by my feelings. I felt devastated.

The women felt ashamed and ended up blaming themselves for what was happening.

His insults relentlessly and systematically were aimed at keeping me where I was ‘cos I was ashamed.

Because you couldnae tell anybody, yer thinking it’s all your fault, you’re just trying to survive …Am Ah imagining this? Whit is it Ah’ve actually done? It was just, things were just…getting worse and worse. When you are in that you don’t think… I think you’re just lost.

All of the women experienced mental health symptoms including depression, severe anxiety, low self-esteem, nightmares and flashbacks but were often at pains to understand what was going on.

I really suffered depression but I didnae seek help for it because I didnae know what it was.

Women’s sense of disempowerment was profound. Their decision-making and personal agency were greatly reduced as their husbands’/partners’ assessment of them penetrated deep into the psyche.

I was emotionally and psychologically destroyed. I didn’t see the fact that I was being persuaded to give up my identity.

Psychologically it was really weird because there were times when I felt I was outside of myself, observing myself and, and disgusted at what I was doing.

These recollections of the traumatic impact of the abuse provide us with glimpses into the psychological struggles women had to overcome before they could even contemplate separation. Those who approached their GPs for their mental health symptoms did not disclose the abuse in their lives and were prescribed anti-depressants, beta-blockers and tranquillisers without further inquiry about their situation. Only one disclosed to her GP who was supportive and offered her counselling.

Steps to Freedom – Stages of Change

Women’s descriptions of the leaving their relationships corresponds almost exactly to the stages of change described by Procasta and DiClemente: pre-contemplation, contemplation, determination, action, maintenance. [ii] For many years, the women endured the violence and abuse and its impact on them in the hope that it would eventually end. Over time, when this did not happen and the endless cycles of violence continued, they gradually gave up hope and began to contemplate leaving.

I think there comes a time when you just know that it’s right to do it. I am not putting up with this anymore.

Yeah, it was constant escape, how would I do that? So I guess it was kinda subconscious but then I think it became more conscious.

The idea of an alternative future free of violence for themselves and their children gradually emerged as a possibility. Seeing the impact on their children was a powerful motivator for many of the women.

I’ve always had a good relationship with my children and that’s why I had to go. I knew that day that I had to protect them. And I didnae care how I was going to do it. That day, I just knew.

The women were now working in better paid jobs, some had careers, were developing interests outside the home and were becoming aware of the contrast between their home lives and the kind of lives they could be living. However, Scottish society by the 1980s and 1990s still did not look kindly on divorced or separated women or those bringing up children on their own. Permanent separation demanded careful planning and the management of a complex range of issues. The reaction of family and friends to the separation also had to be managed. Most risky of all was the post-separation pressure and threats from their ex-husbands/ex-partners. Then as now, separation can be very dangerous for women as violent men begin to lose control.

Stories of survival and recovery

The women in my study created carefully constructed long-term exit plans. The process of separation took time, years in some cases, and many of the women made several attempts before finally succeeding. Whilst coping and managing the long-term traumatic impact of domestic abuse and the strain of keeping their plans hidden from their husbands/partners, the women faced a range of practical obstacles to successful separation. There was a chronic shortage of decent, secure, affordable housing and ensuring they could support themselves and their children was not easy especially with little or no financial support for the children from their husbands. The women also had to disentangle themselves from the family economy and its debts, juggle work, childcare and school hours as well as facing continued abuse and harassment by their ex-husbands/partners. However all of the women in my study succeeded in leaving – eventually – with the help of a small group of trusted friends and family with whom they shared their plans and without approaching an agency for help.

Women leaving an abusive relationship in the late twentieth century therefore faced a range of emotional, psychological, social, economic and practical hurdles on their way to a free, independent and safe life. Overcoming these obstacles took courage, careful planning, time, help from others and access to a range of resources.

Post Script

I hope these accounts have gone some way to answering the question, Why doesn’t she just leave? Ending an intimate relationship at any time is never easy. Leaving a violent relationship in late twentieth century Scotland was especially hard due to the social attitudes and hostility which abused women faced. Although times have changed, domestic abuse is still with us. Women contemplating separation today still face daunting challenges and risks, which require the same determination, courage, planning and support. Leaving is never a one-off decision or event, then or now. However, nowadays women need not do it alone and can reach out to free helplines and support services in every area of Scotland. Social attitudes, agencies and the legal environment in the twenty-first century are much more informed, knowledgeable, sympathetic and skilled in how they support and advocate for women and children affected by domestic abuse. That much has changed for the better. However as the Femicide Report shows, and as the media report almost daily, women remain at risk and not protected enough from male violence, including in their own homes.

When I interviewed the women, their abusive relationships were well in the past and they were living independent, safe and contented lives. Their stories of abuse, survival and recovery in late twentieth century Scotland are truly inspirational. I thank them all for their honesty and courage sharing their life stories with me so willingly and for revisiting some deeply distressing memories. It was a privilege to bear witness to their personal histories. I have shared my findings in my blogs and elsewhere* in tribute to them and to contribute their stories to our knowledge about Scotland’s recent past.

*This research is featured in the BBC Radio Scotland Time Travels Podcast ‘Women, Witchcraft and Violence’.

If you feel scared of your partner or ex-partner, or if you are worried about someone you know, get in touch with Scotland’s 24-hour Domestic Abuse and Forced Marriage Helpline on 0800 027 1234 for support and information. You can also email and web chat from www.sdafmh.org.uk. There are translation and interpreting services available.

[i] Mullender, A. (1996). Rethinking domestic violence: The social work and probation response, Routledge. P.23

[ii] Prochaska, J. O. and DiClemente, C. C. (1982). “Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 19(3): 276-288.