In November 2022 I published a new edition of ‘Sell and be Damned – the great Merrylee housing scandal of 1951’, by my Dad, Ned Donaldson and his pal Les Forster – but the Merrylee story is really three stories in one: it’s personal, it’s political and it’s historical.

The Merrylee protest began toward the end of 1951 and ended successfully in May 1952. The word Merrylee held a story involving the adults in my family which I heard throughout my childhood; it seemed to my wee mind to be important, it was spoken of with pride but, at times, tinged with darker undertones which I didn’t really understand until I was much older. The word Merrylee was one of a number of words in our family’s lexicon alongside socialism, communist, trade unions, the YCL, Daily Worker, May Day, the Cooperative Guild, and the Soviet Weekly. The word communist to my Mum Mary, in particular, was at times something she was simultaneously proud of, yet careful about mentioning in certain circumstances. Making sense of it all took me a while.

It’s just over seventy-one years since the Merrylee protest march in December 1951. In the early 1990s Ned and Les, two politically and historically very savvy guys, knew the 40th anniversary of the protest was coming up and that the story of Merrylee would be forgotten unless somebody wrote it down. Both were highly literate and articulate men, well known for just getting on and doing things, their politics were very practical, very active. They decided to gather the stories, interview those who were involved and write a book about it to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Merrylee in 1992.

‘The ‘Merrylee affair’ receives little mention amongst books concerned with social and political history. Yet housing remains the biggest social issue in Scotland today, and Glasgow’s housing problem is dubbed the worst in Europe. The almost criminal decision to authorise the sale of council housing has only exacerbated the problem.’

Sell and be damned (1992)

‘Sell and be damned – the great Merrylee Housing Scandal of 1951’ is a first-hand account, written by and including the voices of those who were involved in the protest. I felt their story was worth republishing because, apart from a few rough copies, the book was out of print. I decided to celebrate the original protest in 1951 and the publication of the book 30 years ago in early 1992 by bringing out a new edition in 2022.

The Merrylee story itself is told in the book but by weaving the personal, the political and the historical stories which simultaneously run across each other and across time there are perhaps wider meanings to be gleaned for twenty-first century readers.

Politics: Housing for the needy not the greedy!

Merrylee is a story about working-class people whose lives were directly and negatively affected by a policy decision made by local politicians with a clear political agenda completely divorced from the lives it would affect.

As the 1950s dawned, Glasgow, like the rest of the country, was only five years away from the end of the war and the city continued to struggle with its historic legacy of poor housing and housing shortages. There had been no houses built during the war in Glasgow and in 1951, James Duncan a local Baillie commented,’ if the 46,800 homeless people in Glasgow marched three abreast and with a one-yard interval between the ranks, they would form a procession five and a half miles long’. In 1949, the Conservatives (known then as the Progressives [sic]) had taken control of the Corporation. They had spent much of the interwar years opposing the construction of municipal housing in order to keep the rates low for middle class ratepayers (homeowners paid rates, those renting did not). By 1951 – approximately 143,000 of the existing housing stock were either single ends or one bedroom flats and Glasgow needed 186,000 houses. In the 1951 city housing plan, 169,000 existing houses were to be demolished but only an additional 17,000 new houses built. This exacerbated class tensions in the city.

Workers engaged in post-war reconstruction needed homes, and the labour movement was energetic in the cause of homelessness alongside the tenants’ associations which became active at the time. New homes were needed but over-crowding, insanitary conditions and sub-let racketeering by unscrupulous landlords were longstanding and persistent problems in Glasgow. Housing was a class and a labour issue with council housing yet again at the forefront of politics as it had been in the interwar years.

Towards the end of 1951 when the Corporation decided to sell the 622 houses that they were building at Merrylee and, given the shortage of housing, workers in the Corporation’s Direct Labour Department who were building the houses were incensed.

The shop stewards at Weirs Engineering convened a conference of all delegates in the city’s trade union movement to oppose the sale. However, Ned, Les and others were concerned that the ‘traditionalists’ in the unions and the labour movement would put their faith in the local elections due in May 1952. The Glasgow Trades Council and many union branches favoured making requests for deputations to the Corporation. Les and Ned worried that the call to action would lead

to direct action or fall into the deadening clutch of officialdom, ‘this sort of thing would not raise much of a flutter in their pigeon-holes.

Sell and be damned 1992

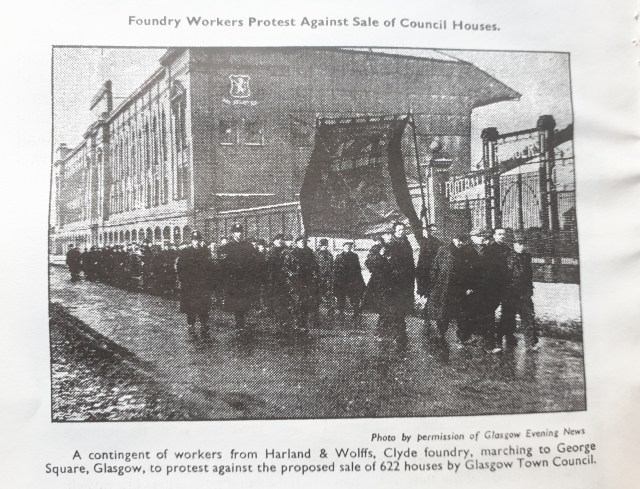

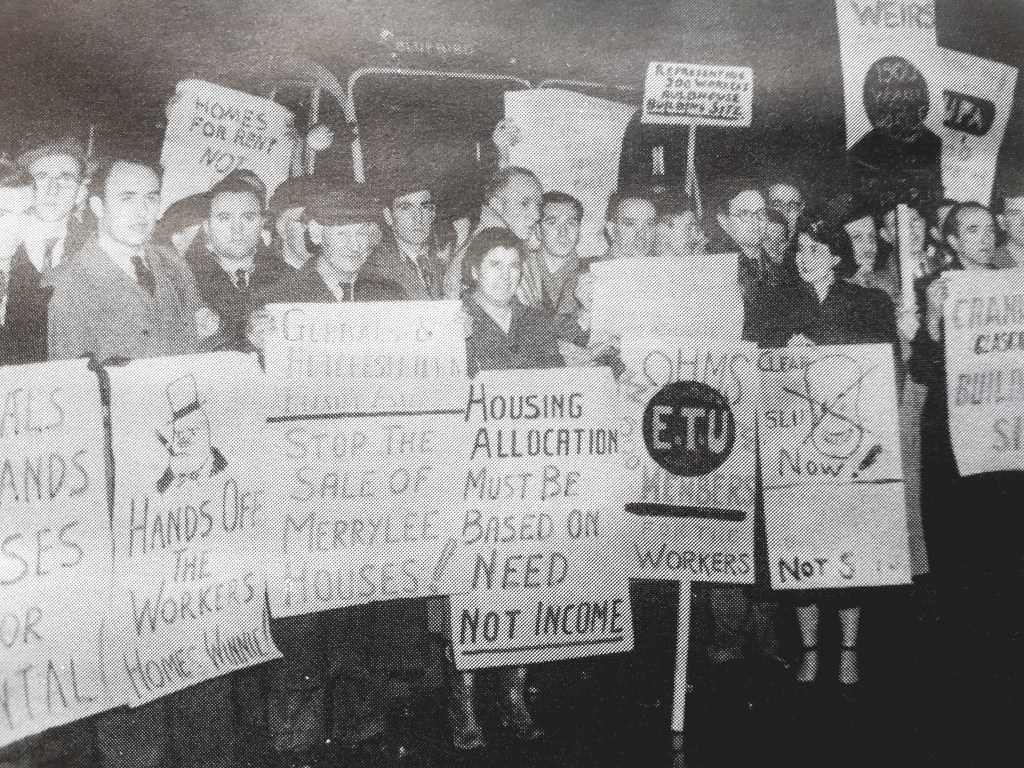

The workers had other ideas: on the day the Merrylee motion was to be discussed in the City Chambers, 6 December 1951, the workers planned direct action organised by federation shop stewards who were a strong network across all sectors in the city – a one day strike and a march on George Square.

The bricklayers, plumbers, painters, electricians, dumper drivers, navvies, plasterers downed tools. Foundry workers from works across the city, railwaymen, engineering workers from Weirs Pumps as well as tenants’ associations converged on the city centre. It was decided that the Cranhill contingent with their model house would lead the march. Officials of the Glasgow Trades Council standing on the pavement sent round to their office for the official banner and made a move to lead the demonstration. They were told in no uncertain terms that they were welcome to join the march but they would not be leading it. This was direct action organised by the workers themselves outside the official channels inhabited by the ‘traditionalists’ among the trade union movement.

While the Corporation meeting was going on inside the Chambers, estimates vary but between 700 and 2000 marchers went around the square three times and held a rally in North Frederick St. Many speakers addressed the crowd including women from tenants’ associations who spoke about the conditions of their homes with one woman from the Gorbals holding up a dead rat and another a lump of sodden plaster from her home.

The Corporation motion was carried but during the following months, campaigning and protest continued to grow with the City’s Labour Party and Trades Council voting to back the struggle in January. The campaign has been regarded by some as a factor in the Labour Party regaining control of the Corporation in the May elections.

Personal

Ned and Les’ activism came at a personal cost. As the campaign continued into 1952, victimisation began on sites. Les and several other leading shop stewards were sacked and Ned was blacklisted from working in the Corporation and on other sites in the city. The official trade union movement give them no backing and he found himself isolated and unemployed even although there was a shortage of skilled labour. He had to seek employment outside the city. For a young man of 24, now married to Mary and with a new baby, times were very tough. Talk of Merrylee around me as I grew up was thus tinged with the economic and political consequences it had for my Mum and Dad and their comrades.

For Ned, the existential struggle for public housing went hand in hand with struggle to unionise the construction industry. In his memoirs, he recalled that the general swing to the right in British and international politics at the time meant the left wing was under attack all over the world – anti-communist hysteria had reached fever level. He also spoke about witch hunts in the trade unions including the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) which banned members of the Communist Party (CP) like himslef and others from holding office.

Ned and Les’ personal integrity, independence of mind and support for direct action in the Merrylee campaign also created problems for them with the CP hierarchy in Glasgow. Unhappy with the ‘cult of the individual’ surrounding Stalin and the reformist direction the party was taking – including a move towards a parliamentary road to socialism – Ned and Les joined Harry McShane, Hugh Savage, Jeanette and Matt McGinn and others in quitting the party in 1952.

For me the term ‘communist’ was associated in my young mind with pride in my family’s youthful activism in the Young Communist League (YCL) and in the Party in the late 40s until they left after Merrylee debacle. Alongside the blacklisting and the chilly Cold War climate, communism and the Soviet Union became conflated in the mind of the general public and it was very tough for young activists in my family and their friends to find a place for their politics. They were all now seasoned campaigners, union organisers, administrators and public speakers and over the years they eventually found other avenues for their political energies including the Cooperative Movement, community-ased housing associations, Workers City and in a trade union movement that eventually got over itself and readmitted them.

History

As I embarked on this project to republish ‘Sell and be Damned’ in 2021, I contacted historian colleagues and housing activists to see if there might be value in doing so. Their enthusiasm for my project came as a huge surprise. It seems that ‘Sell and be damned’, this wee book Ned, Les and the others made has become an important primary source and the story it tells so powerfully, has taken its place as a key moment in the history of working class protest, housing and community campaigns in this city. In a time-line that began with the rent strikes of 1915, on to the squatting movements, to Merrylee, continued with the housing and community struggles and occupations in the Gorbals and Castlemilk in the 1980s, in Kinning Park, at the Govanhill Baths, and on to the present day with the ongoing activism of tenants in the Wyndford area of Maryhill trying to save homes from demolition – housing activism continues and its history inspires. PHDs have covered it, academics have researched it, written and given lectures about it. The twenty-first century tenants’ rights movement such as, for example, Living Rent, takes great inspiration from it. A new archive of housing activism is making sure these stories of working class housing campaigns are preserved for future generations. Without the original publication of the book in 1992, Merrylee might have remained a powerful family story for me and for the families of those involved, a precious and precarious oral history of the working class in Glasgow. My hope is that by reprising and republishing the Merrylee story, the energy and optimism of the Merrylee protesters can be kept alive and continue to inspire others for at least another seventy years.

Some readers may think that the Merrylee struggle was in vain: eventually Glasgow gave in to the Thatcher Tories and sold council houses. What they did was unforgiveable. There are no cobwebs upon the events described in this book.

It is a relevant and significant story for today.’

Sell and be damned (1992)The new expanded edition contains additional material by James Kelman and Dr Valerie Wright for which I am very grateful. Its publication was made possible with the financial support of a number of individuals and organisations – all named in the new edition. I am extremely grateful to all of them and to the Scottish Labour History Society for publishing the new edition

Donaldson, E, Forster, L., (1992), Sell and be damned, the great Merrylee housing scandal of 1951. (New Edition, Donaldson, A. (Ed). 2022). Glasgow, Scottish Labour History Society. ISBN 978-1-9163050-3-8

Copies of the new edition of Sell and be damned… can be purchased from:

https://www.akuk.com/sell-and-be-damned-the-glasgow-merrylee-housing-scandal-of-1951.html

Links to further information

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12013385.ned-donaldson/

http://www.workerscity.org/the_reckoning/ned_donaldson.html

https://mapmagazine.co.uk/tenancy-x-document-stock-transfer

Herald article 16 January 2019

Ned Donaldson, Homes for the Needy – Workers City

http://www.workerscity.org/the_reckoning/ned_donaldson.html

Article and photo of Merrylee

https://www.theglasgowstory.com/image/?inum=TGSA05283

Let Glasgow Flourish film

https://movingimage.nls.uk/film/1721

glasgowtennantsarchive.com

Occupy! Occupy! Occupy! Comic Book, (2022), 36 page comic book in collaboration with; Magic Torch Comic, featuring industrial, community, student and environmental occupations in Scotland from the 1940s till now. Glasgow. Govanhill Baths Trust. https://www.govanhillbaths.com/product/occupy-occupy-occupy-comic-book/

Further reading

Damer, S. (1990) Glasgow: Going for a Song, London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Damer .S (2020), Scheming. A social history of Glasgow council housing 1919-1956. Edinburgh University Press. Edinburgh.

Johnstone, C. (1992) ‘The Tenants’ Movement and Housing Struggles in Glasgow, 1945-1990’. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Glasgow.

Michael Lavalette & Gerry Mooney (eds.) (2000): Class Struggle and Social Welfare, Routledge. Especially Chapter 8: ‘Housing and class struggles in post-war Glasgow.’

Wright, V. (2018), ‘Housing problems … are political dynamite’: housing disputes in Glasgow c. 1971 to the present day. Sociological Research Online, (doi:10.1177/1360780418780038.